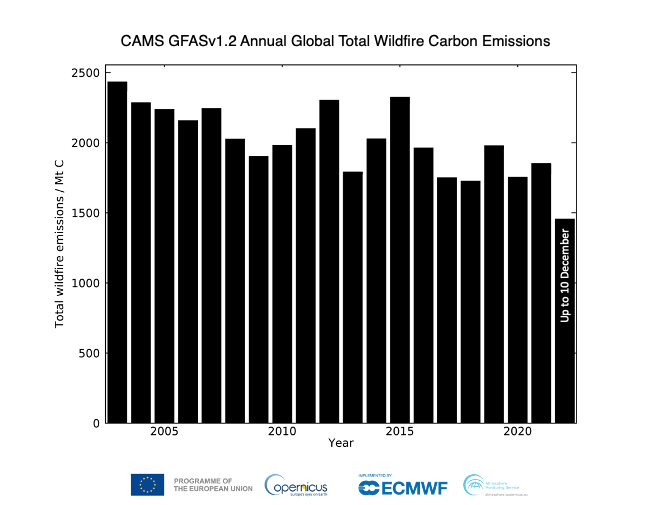

Wenn wieder mal irgendwo auf der Erde ein Waldbrand wütet, ist der Verursacher schnell gefunden: Der Klimawandel. Wenn dem so wäre, müsste es aber immer mehr Waldbrände mit immer mehr dadurch verursachte Emissionen geben. Stimmt das? Copernicus hat die globale Entwicklung der CO2-Emissionen aus Waldbränden dargestellt:

Der Trend geht klar nach unten. Aus Waldbränden wird immer weniger CO2 freigesetzt. Wieder ein Mythos aus der Alarm-Presse beerdigt.

+++

Ähnlich sieht es bei Überschwemmungen aus. Auch hier wird gerne der Klimawandel als Haupt-Beschleuniger präsentiert. Lancaster University hat nun aber einen ganz anderen Faktor ausgemacht. Die stete Ausweitung der extensiven Landwirtschaft macht die großen Ebenen in Südamerika anfälliger für Überschwemmungen. Wo früher Bäume die Wassermassen gebremst haben, kann sich das Wasser heute leicht ausbreiten und die Landschaft verwüsten. Irgendwie logisch. Hier die Pressemitteilung von Lancaster University:

Expanding large-scale agriculture is escalating flooding in the largest South American breadbasket

A new study revealing that huge expansions of extensive large-scale agriculture is making the South American plains more vulnerable to widespread flooding should act as a „wake-up call,“ say researchers.

The grasslands of the Argentinean Pampas, famously home to the iconic Gaucho, along with other extensive flat plain areas of South America have been undergoing an intense transformation in recent decades.

Driven by soaring international demand, extensive areas of grasslands, and forests across South American plains have rapidly been converted to the production of annual crops, such as soybean and maize. This agricultural expansion has been taking place at a staggering rate of 2.1 million hectares a year.

Environmental concerns around biodiversity and soil degradation from these changes are long-standing. However, a new study, published in Science, shows how these shifts to annual crop agriculture, which relies on rainfall rather than irrigation, is also rapidly disrupting the water table across the large flat regions of the Pampas and Chaco plains and contributing to significantly increased risks of surface flooding.

The international team of researchers from universities of San Luis in Argentina and Lancaster University in the UK used satellite imagery and field observations over the last four decades, as well as statistical modeling and hydrological simulations, to identify trends for groundwater and flooding. They revealed unprecedented evidence on how subtle, but widespread changes to vegetation cover by people, can transform the water cycle across large regions.

„The replacement of native vegetation and pastures with rain-fed croplands in South America’s major grain-producing area has resulted in a significant increase in the number of floods, and the area they affect,“ said Dr. Javier Houspanossian of the National University of San Luis, in Argentina. „Fine-resolution remote sensing imagery captured the appearance of new flooded areas, expanding at a rate of approximately 700 square kilometers per year in the central plains, a phenomenon unseen elsewhere on the continent.“

The data revealed that as short-rooted annual crops replace deeper-rooted native vegetation and pastures, floods are gradually doubling their coverage and becoming more sensitive to changes in precipitation. Groundwater, once deep beneath the surface (12–6 meters), is now rising to shallower levels (around 4 meters).

„By replacing deeper rooted trees, plants and grasses with shallow rooted annual crops over such a huge scale this has culminated in seeing the regional water table rise closer to the surface,“ said Dr. Esteban Jobbágy of CONICET, in Argentina. „As the water level rises closer to the surface there is naturally less capacity for the land to absorb heavy rainfall, contributing to making flooding more likely.“

The key to this sensitivity to shallower water tables is the flatness of the land, as this results in water that is very slow at flowing away. And the flattest sedimentary plains also happen, in many cases, to host some of the best farming soils on Earth.

„In these extremely flat regions we find vegetation changes play a major role in modulating flooding through the capacity of plants to draw down groundwater reserves during dry periods,“ said Dr. Jobbágy.

The researchers say these findings are a „wake-up call“ that show that by rapidly expanding agriculture across wide plains, people can disrupt the hydrology across a large scale, increasing the risks of flooding.

„These floods are a major concern for the farmers and people living in the region, but also elsewhere as further expansions of these floods could potentially disrupt food supplies and prices,“ said Professor Mariana Rufino, formerly of Lancaster University.

„These results should act as a wake-up call that if we are going to make such huge and rapid land-use changes across large flat landscapes then it can transform the hydrology with potential increased risks.“

In addition to flooding, researchers say these human-induced hydrological changes are also risking other issues such as soil erosion, methane emissions and salting of the land through salination.

The researchers argue that the hydrological changes happening in the South American plains also offer lessons for other similar agriculturally intensifying flat regions elsewhere in the world, such as central Canada, Hungary, Kazakhstan, areas of China and the Ukraine.

Professor Peter Atkinson of Lancaster University said, „This research reminds us that the Earth is a delicately balanced system, and that our actions in one domain can have unintended negative consequences in another, in this case fairly uniformly over a vast area.“

Dr. Wlodek Tych of Lancaster University said, „We used a statistical modeling approach that avoided bias and strong assumptions, adding rigor to our findings linking intensive agriculture expansion to increased risk of flooding. These findings should inform new land management policies across these extensive flat rain-fed regions.“

The authors say the findings underscore the urgent need for smarter land use policies that promote sustainable farming practices and informed water management strategies.

„There is much that can be done at the landscape level if we allocate parts of the land to deep rooted forest patches, and perennial pastures to prevent very shallow areas of ground water,“ said Dr. Jobbágy.

Other solutions include breeding crops with deeper root systems, crop rotations more flexible to water table depths. The findings are outlined in the paper „Agricultural expansion raises groundwater and increases flooding in the South American plains“ published by Science.

Paper: Javier Houspanossian et al, Agricultural expansion raises groundwater and increases flooding in the South American plains, Science (2023). DOI: 10.1126/science.add5462. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.add5462

+++

Leibniz-Institut für Troposphärenforschung e. V.:

Rauch von kanadischen Waldbränden schwebt seit Wochen über Deutschland.

Neues Verfahren verbessert den Nachweis von Rauchpartikeln in der Atmosphäre.

Leipzig. Riesige Waldbrände in Kanada haben Millionen von Hektar Wald vernichtet, mehr als 100 000 Einwohner vertrieben und die Luftqualität von Millionen Menschen in Nordamerika beeinträchtigt. Die Spuren dieses ökologischen Desasters sind auch in der Atmosphäre über Deutschland zu spüren: Seit Mitte Mai registrieren Forschende des Leibniz-Instituts für Troposphärenforschung (TROPOS) regelmäßig dünne Rauchschichten in Höhen zwischen 3 und 12 Kilometern Höhe über Leipzig. Der Nachweis, dass es sich bei den Partikeln um Rauch aus Waldbränden handelt, wurde durch eine neue Technik möglich: Rauchpartikel sind biologischen Ursprungs und leuchten, wenn sie mit UV-Licht eines Lasers angestrahlt werden. Durch können sie eindeutig von anderen Teilchen wie Vulkanpartikeln oder Saharastaub unterschieden werden. Der Ursprung der Rauchschichten konnte anhand der Luftströmungen bis nach Nordamerika zurückverfolgt werden.

„Es ist beeindruckend und beängstigend zu gleich, zu sehen, welche Dimensionen diese Waldbrände inzwischen erreicht haben: Wenn in Kanada und den USA wochenlang Wäldern brennen, dann leiden nicht nur die Menschen dort unter dieser Katastrophe. Auch die Atmosphäre über Europa wird beeinflusst: In den hohen, normalerweise wolkenfreien Luftschichten scheinen sich durch die Rauchpartikel dünne Schleierwolken zu bilden“, berichtet Benedikt Gast vom TROPOS, der die aktuellen Messungen im Rahmen einer Doktorarbeit betreut und auswertet.

Im Gegensatz zu Nordamerika, wo im Juni unter anderen die Millionenmetropolen der Ostküste tagelang unter einer Rauchglocke lagen und Feinstaubalarm herrschte, stellt der Rauch aus Nordamerika in Europa zur Zeit keine Gesundheitsgefahr dar. Der Rauch schwebt in großen Höhen und ist inzwischen stark verdünnt. Aber er beeinflusst die Atmosphäre und das Klima: Zum einen wird die Sonnenstrahlung an den Partikeln gestreut und das Licht so leicht gedimmt. Ähnlich wie bei Saharastaub kann der Himmel ebenfalls leicht getrübt aussehen. Außerdem könnte der Rauch die Wolkenbildung in höheren Schichten der Atmosphäre beeinflussen. Zumindest deuten jüngste Forschungsergebnisse darauf hin: Während der MOSAiC-Expedition in der Arktis 2020 konnten TROPOS-Forschende ungewöhnlich viel Rauch in der Atmosphäre um den Nordpol messen und die Bildung von Zirruswolken beobachten. Eine aktuelle Studie aus Zypern zeigt, dass Rauchpartikel unter bestimmten Voraussetzungen als Nukleationskeime für die Bildung von Eiskristallen wirken können. Dazu hatten die Forschenden des Eratosthenes Centre of Excellence, der Cyprus University of Technology und des TROPOS Daten aus Limassol vom Herbst 2020 ausgewertet als der Rauch starker Waldbrände aus Nordamerika bis ans Mittelmeer von Portugal bis nach Zypern transportiert wurde. Die Messungen damals lieferten deutliche Hinweise, dass gealterte Rauchpartikel bei rund -50°C die Eisbildung am Übergang zwischen der feuchten Troposphäre und der trockenen Stratosphäre auslösten und so zur Bildung von Eiswolken führten.

„Auch unsere aktuellen Beobachtungen über Leipzig zeigen Hinweise auf einen solchen Zusammenhang. Bei mehreren Messungen in den letzten Wochen konnten wir in 10-12 km Höhe sowohl Rauchschichten als auch an deren Unterkante und/oder direkt darunter Eiswolken (sogenannte Zirren) beobachten. Solche Rauch-Schichten in starker Präsenz von Zirruswolken wurden nicht nur in Leipzig, sondern auch an verschiedenen Stationen in Europa beobachtet: Von Südwesten in Evora (Portugal), über Warschau (Polen) bis Kuopio (Finnland) im Nordosten. Sollte der Rauch für mehr Wolken sorgen, könnte dies einen neuen Wirkungspfad für Klimaveränderungen bedeuten. Da Wolken, je nach ihren optischen Dicken und anderen Eigenschaften, eine kühlende oder wärmende Wirkung haben können, könnten sich somit häufigere und stärkere Waldbrände entsprechend auf den atmosphärischen Strahlungshaushalt auswirken. Dieses Potential motiviert uns, dieses Zusammenspiel von Waldbrandrauch und Wolkenbildung weiter zu untersuchen“, sagt Benedikt Gast vom TROPOS.

Durch den Klimawandel nehmen Anzahl und Intensität von Waldbränden zu und damit auch die Mengen an Aerosol, die bei der Verbrennung von Biomasse in die Atmosphäre freigesetzt werden. Diese Aerosolpartikel können nicht nur in der Troposphäre verteilt werden, sondern sogar die darüber gelegene Stratosphäre erreichen und den Strahlungshaushalt der Erde sowie die Wolkenbedeckung über lange Zeiträume und große Gebiete hinweg beeinflussen. „Seit Beginn der Waldbrandsaison 2023 auf der Nordhalbkugel haben wir Rauch in fast jeder Schicht der Atmosphäre gesehen, auch in der unteren Stratosphäre. Aus Sicht der Atmosphärenforschung ist das ein beunruhigender Trend: Die Klimaerwärmung scheint nicht nur dafür zu sorgen, dass die großen Wälder am Rande des Polarkreises immer häufiger und stärker brennen. Sie verändert auch unsere Atmosphäre signifikant und beeinflusst wiederum das Klima. Dazu kommt, dass vieles dafür spricht, dass der Rauch auch die Ozonschicht angreift und damit ein Gesundheitsrisiko für Millionen Menschen darstellt“, erklärt Dr. Albert Ansmann vom TROPOS.

Um die Auswirkungen von Aerosolen auf das Klima vollständig zu verstehen und zu quantifizieren, ist eine genaue Aerosoltypisierung von entscheidender Bedeutung. Multiwellenlängen-Polarisations-Lidare, wie sie TROPOS an verschiedenen Standorten betreibt, sind dabei sehr leistungsfähige Instrumente zur Erkennung und Klassifizierung von Aerosol mit Parametern wie dem Lidarverhältnis, dem Depolarisationsverhältnis und dem Ångström-Exponenten. Allerdings war es bisher schwierig, stratosphärischen Rauch von vulkanischem Sulfataerosol zu unterscheiden.

Jüngste Studien haben gezeigt, dass die Fluoreszenzlidar-Technik ein großes Potential zur Verbesserung der Aerosolklassifizierung hat, weil damit ein weiterer Parameter zur Verfügung steht – die so genannte Fluoreszenzkapazität (Verhältnis von Fluoreszenz-Rückstreuung zu elastischen Rückstreukoeffizienten). Die Forschenden haben deshalb ihren großen, stationären Atmosphärenlaser am TROPOS in Leipzig erweitert: Das „Multiwavelength Atmospheric Raman Lidar for Temperature, Humidity, and Aerosol Profiling“ (MARTHA) erhielt im August 2022 einen zusätzlichen Empfangskanal, der die Fluoreszenz-Rückstreuung im Spektralbereich von 444 – 488 Nanometer messen kann. Die Erfahrung mit der neuen Technik zeigt, dass das Fluoreszenzlidar nicht nur großes Potential für die Aerosoltypisierung hat, sondern auch, um Rauchschichten überhaupt zu finden. „Da der neue Kanal nur sensitiv für Partikelstreuung ist, ist er perfekt geeignet für Aerosol-Profiling. Das haben mehrere Fälle bereits bewiesen. Fluoreszenz ist wie ein Fernglas für das Lidar“, berichtet Dr. Cristofer Jimenez vom TROPOS. „Besonders bei niedrigen Aerosol-Konzentrationen kann ein Fluoreszenzlidar interessante und ganz neue Ergebnisse ermöglichen. Von dieser Technik ist noch viel zu erwarten.”

Ein leistungsstärkerer Laser, mit dem auch noch höhere Schichten der Atmosphäre und geringere Konzentrationen untersucht werden können, soll in den nächsten Monaten folgen. Sowohl die Station in Leipzig als auch die in Limassol gehören zu PollyNet, einem Netzwerk von Lidaren, die mit Laserstrahlen die Atmosphäre vom Boden aus erforschen. Es ist Teil der Europäischen Forschungsinfrastruktur ACTRIS, die Aerosole, Wolken und Spurengase untersucht.

+++

Gute Nachrichten vom Erie See in Nordamerika: Die Algenblüte ist weniger intensive als normal. Zuviel „good news“. Die deutsche Presse schweigt dazu. Sie bringe lieber Katastrophen News. Noch 2015 schockierte der Spiegel seine Leser mit einem Grusel-Artikel zum total durch Algenblüte vergrünten Lake Erie. Heute, 2023, wird es voraussichtlich viel besser ausgehen. Hier die Pressemitteilung der University of Michigan:

Smaller-than-average harmful algal bloom predicted for western Lake Erie

NOAA and its research partners, including the University of Michigan, are forecasting that western Lake Erie will experience a smaller-than-average harmful algal bloom this summer, which would make it less severe than 2022.

This year’s bloom is expected to measure 3, with a potential range of 2-4.5 on the severity index, whereas last year’s bloom was measured at a 6.8, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced today.

The index is based on the bloom’s biomass—the amount of algae—during the peak 30 days of the bloom. An index above 5 indicates more severe blooms. Blooms over 7 are particularly severe, with extensive scum formation and coverage affecting the lake. The largest blooms occurred in 2011, with a severity index of 10; and 2015, with a severity index of 10.5.

„While this year’s forecast is smaller than the long-term average, it was driven primarily by the lowest river flows in the past 10 years. We cannot just cross our fingers and hope that drier weather will keep us safe,“ said U-M aquatic ecologist Don Scavia, a member of the forecast team.

„These blooms are driven by diffuse phosphorus sources from the agriculturally dominated Maumee River watershed. Until the phosphorus inputs are reduced significantly and consistently so that only the mildest blooms occur, the people, the ecosystem and the economy of this region are being threatened,“ said Scavia, professor emeritus at the School for Environment and Sustainability.

Lake Erie harmful algal blooms consisting of cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, are capable of producing microcystin, a known liver toxin that poses a risk to human and wildlife health. Such blooms may force cities and local governments to treat drinking water and to close beaches, and they can harm vital local economies by preventing people from fishing, swimming, boating and visiting the shoreline.

The size of a bloom isn’t necessarily an indication of how toxic it is. For example, the toxins in a large bloom may not be as concentrated as in a smaller bloom. Each algal bloom is unique in terms of size, toxicity and ultimately its impact on local communities.

„By consistently improving the science behind our forecasts, we’re giving Great Lakes communities the information they need to plan for blooms of varying severity,“ said Nicole LeBoeuf, director of NOAA’s National Ocean Service. „Understanding and addressing hazards such as harmful algal blooms can help us ensure that the Great Lakes are an engine of the blue econom“

NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science’s Lake Erie HAB Forecast website provides predictions and visualizations of the bloom’s location and movement on the lake’s surface as well as where the bloom is located within the water column. This information is especially helpful to water treatment plant operators, because intake structures are usually located below the surface, so the risk of toxins in their source water may be greater when these cells sink.

„NCCOS’s Lake Erie HAB Forecast continues to be a valuable resource for Lake Erie residents, visitors, and the state,“ said Christopher Winslow, director of Ohio Sea Grant and Ohio State University’s Stone Laboratory. „This NOAA forecast, and the research being conducted by academic institutions and both state and federal agencies to understand blooms and nutrient runoff, will continue to guide efforts to address these summer bloom events.“

NOAA expects a start of the visible bloom in mid-to-late July. The duration of the bloom depends on the frequency of wind events in September, which cannot be predicted this far in advance. The bloom will remain mostly in areas of the western basin. The lake’s central and eastern basins are usually unaffected, although localized blooms may occur around some of the rivers after summer rainstorms.

The range in forecasted severity reflects the uncertainty in forecasting precipitation, particularly for late June and July. Larger rain events during the summer could result in increased river flow, and a higher severity index. NOAA will issue a seasonal forecast update in early August based on observed rainfall in the basin.

„While this spring has been quite dry, the lake received a large nutrient load in March, which will produce at least a mild bloom this summer,“ said Richard Stumpf, NCCOS’s lead scientist for the seasonal Lake Erie bloom forecast. „However, like recent years, we have a potential of additional nutrient load in July, which could lead to a moderate bloom.“

The Lake Erie forecast is part of a NOAA Ecological Forecasting initiative, which aims to deliver accurate, relevant, timely and reliable ecological forecasts directly to coastal resource managers, public health officials and the public. In addition to the early season projections from NOAA and its partners, NOAA also issues HABs forecasts during the bloom season. These forecasts provide the current extent and five-day outlooks of where the bloom will travel and what concentrations are likely to be seen, allowing local decision-makers to make informed management decisions.

In addition, NOAA is developing tools to detect and predict how toxic blooms will be.

Nutrient load data for the forecasts came from Heidelberg University in Ohio. The various forecast models are run by NCCOS, the University of Michigan, North Carolina State University, LimnoTech, Stanford University and the Carnegie Institution for Science.

Field observations used for monitoring and modeling are done in partnership with a number of NOAA services, including its Ohio River Forecast Center, NCCOS, the Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services, and the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, as well as the University of Michigan-based Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research, Ohio Sea Grant, Stone Laboratory, the University of Toledo, and Ohio EPA.