Von Frank Bosse

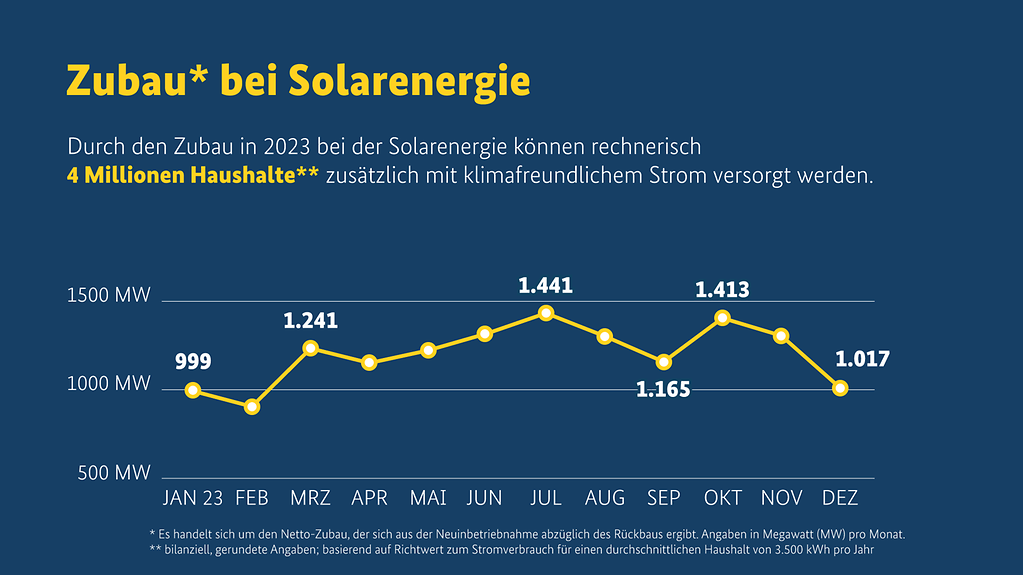

Die Bedingungen für die Gewinnung von Strom aus Photovoltaik sind im Juli naturgemäß ganz hervorragend. Die Sonne steht hoch und lange am Firmament und die verbaute Fläche für Solaranlagen nimmt stark zu, so die Bundesregierung:

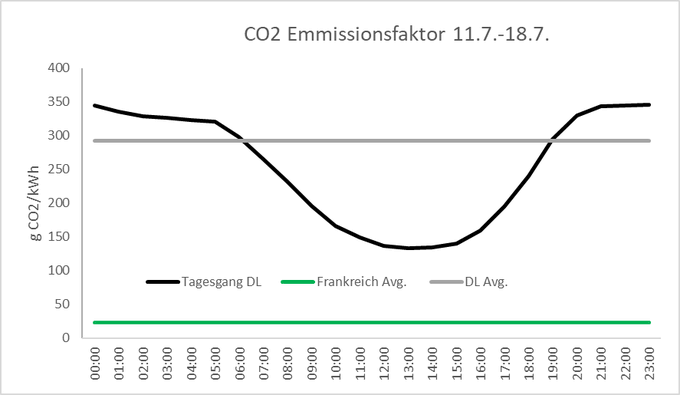

Eine gute Gelegenheit also, die Erfolge beim „CO2-Emissionsfaktor“ zu feiern? Er sagt aus, wieviel g CO2/kWh produziertem Strom ausgestoßen wird. Photovoltaik (und Wind sowie Wasserkraft) glänzen hier mit angenommenen Null-Emissionen. Um eine Prüfung zu unternehmen, kann man bei „Agora“ stundengenaue Daten ansehen und herunterladen. Da auch im Juli das Wetter unterschiedlich sein kann und man diese Einflüsse herausmitteln sollte, schauten wir uns die Zeit zwischen dem 11. Juli 2024 und dem 18.Juli 2024 an:

Die Aussagen der Erhebung müssen für Deutschland beunruhigen: In der dunklen Tageszeit werden bis zu 350 g CO2 /kWh ausgestoßen, auch in der Mittageszeit sind es noch über 100 g CO2/kWh im Wochenmittel. Der Mittelwert über die Tage (grau) beträgt denn auch knapp 300 g CO2/kWh.

Zum Vergleich ist dieses Mittel für Frankreich in grün (Daten) mit verzeichnet, es sind ca. 23g CO2/kWh.

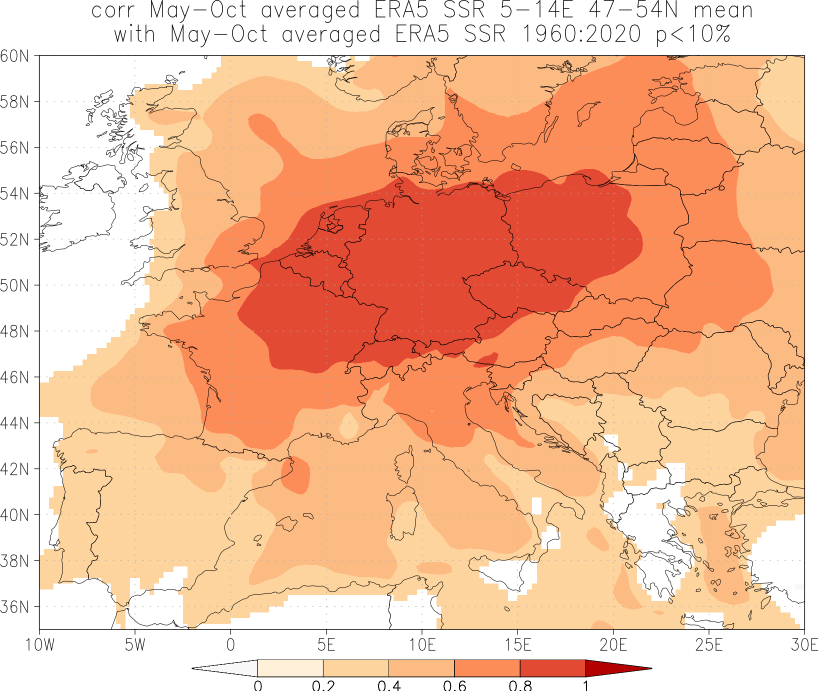

Deutschland ist weit weg von „sauberer Energie“ und in Punkto „Klimaneutralität“ sehr weit zurück im internationalen Vergleich. Hinzu kommt, dass es mit den vielen „Balkonkraftwerken“ zunehmend Probleme gibt: Sie sind nicht zentral zu managen und bei weiterem Ausbau wird geschätzt, dass es schon in 2 Jahren zu erheblichen Problemen bei der Netzstabilität kommen wird, da sie oft viel Strom produzieren, wenn er nicht gebraucht wird und man den kaum loswird. Der Grund hierfür: In der “hellen Jahreszeit” korreliert die Sonneneinstrahlung in Deutschland sehr hoch mit unseren Nachbarn:

Die Korrelationen des Sonnenscheins (SSR für “Shortwave Solar Radiation”) in Deutschland zu dem Rest von Europa. Die Abbildung wurde mit dem KNMI-Climate Explorer generiert.

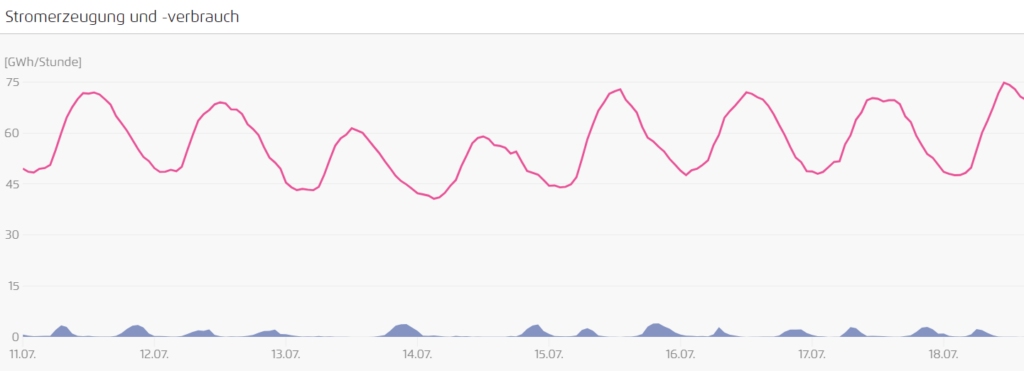

Die „Deutsche Energiewende“ scheint in eine Sackgasse zu steuern: Das alleinige Setzen auf Energien niedriger Dichte mit hoher Volatilität braucht Speicher, die es schlicht nicht in auch nur annähernd ausreichendem Maße gibt. Dann muss immer CO2-intensive Stromproduktion aushelfen. Man liest, dass es bald (2027) gelingen soll, die Kapazität von Batteriespeichern in die Größenordnung der vorhandenen Pumpspeicherwerke zu bringen. Was das bedeutet, kann man auch bei „Agora“ nachschauen:

(Screenshot Agora)

Erkennen Sie den Beitrag, den Pumpspeicher (grau) gegenwärtig zum Energieverbrauch (violett) leisten können? Es sind maximal ca. 10%, das ist ein Tropfen auf den heißen Stein! Man sollte Wetten darauf abschließen, wann der Deutsche Weg hin zu real klimaschonender Stromproduktion geändert werden muss. Weil die Erfolgsaussichten des bisherigen nahe null sind.

+++

Markus Krall auf Youtube:

+++

Unusual rainfall brings winter flowers to Chile’s Atacama desert

Large swaths of the Atacama desert, the driest on the planet, have been covered with purple and white flowers after unusual rainfall patterns in northern Chile.

Weiterlesen auf phys.org:

+++

Jack Marley auf The Conversation:

Earth is getting hotter – so why is this summer so dismal?

Fossil fuels have kept Earth 1.5°C hotter than its pre-industrial average temperature for more than a year now.

And yet, where I live in the UK, this summer has felt like one of the coolest I can remember. If the planet is in the middle of “a large and continuing shift” to a hotter climate as scientists say it is, why is the weather so cold during what is supposed to be the warmest time of year?

Satisfactory answers to questions like this can nip climate scepticism in the bud. Luckily, the experts we’ll hear from today have plenty.

Matthew Patterson is an atmospheric physicist at the University of Reading. He says that the UK’s dismal summer hasn’t been unusually cold – in fact, measurements of temperature, sunlight and rainfall in June 2024 were all close to their seasonal averages.

Unfortunately, “average” conditions now feel colder than they used to.

Weiterlesen auf The Conversation:

+++

Leah Burrows, Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences:

Warming Arctic reduces dust levels in parts of the planet, study finds

Climate change is a global phenomenon, but its impacts are felt at a very local level. Take, for example, dust. Dust can have a huge impact on local air quality, food security, energy supply and public health. Yet, little is known about how global climate change is impacting dust levels.

Previous studies have found that dust levels are actually decreasing across India, particularly northern India, the Persian Gulf Coast and much of the Middle East, but the reason has remained unclear. Researchers at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) are working to understand how global climate change is impacting dust levels in the region.

In a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of researchers led by Michael B. McElroy, the Gilbert Butler Professor of Environmental Studies at SEAS, found that the decrease in dust can be attributed to the Arctic warming much faster than the rest of the planet, a phenomenon known as Arctic amplification.

This process destabilizes the jet stream and changes storm tracks and wind patterns over the major sources of dust in West and South Asia—namely the Arabian Peninsula and the Thar Desert between India and Pakistan.

„Local land management, rapid urbanization and industrialization certainly contribute to dust levels West and South Asia but the novel insight from our study is the increasingly dominant influence of circulation change on the broader global climate context,“ said McElroy.

„Changes in atmospheric circulation patterns, driven by global climate dynamics shifts, have emerged as the principal driver behind the observed recent dust reductions in West and South Asia.“

What does that mean for the future of dust in the region? It all depends on how we curb emissions. Ironically, the best-case scenario for emissions—carbon neutrality—could have the worst impact for dust. If humans can reduce emissions enough to slow or stop Arctic amplification, then the jet stream and wind patterns would likely return to pre-warming states, which would lead to an increase in dust.

Of course, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t pursue carbon neutrality, said McElroy. But as the global community works to reduce greenhouse emissions, local governments should simultaneously be working to address dust reduction.

„At the local level, we need to be thinking about stronger anti-desertification actions such as reforestation and irrigation management and how to better monitor urban-level dust concentrations, in concert with broad climate mitigation strategies,“ said McElroy.

The research was co-authored by Fan Wang, Yangyang Xu, Piyushkumar N. Patel, Ritesh Gautam, Meng Gao, Cheng Liu, Yihui Ding, Haishan Chen, Yuanjian Yang, Yuyu Zhou and Gregory R. Carmichael.

Paper: Fan Wang et al, Arctic amplification–induced decline in West and South Asia dust warrants stronger antidesertification toward carbon neutrality, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2317444121