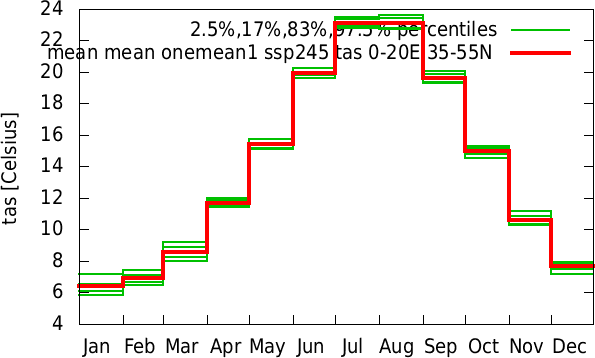

Auf t-online warnt die Meteorologin Michaela Koschak (Vita findet sich dort auch, sie tritt in mehreren TV-Programmen auf) „Die Jahreszeiten in Deutschland werden sich laut einer Expertin im Video radikal wandeln.“ Was ist dran? Hier der Jahresgang für Mitteleuropa in Klimamodellen (CMIP6 Multi-Modell-Mean) für 2010..2020:

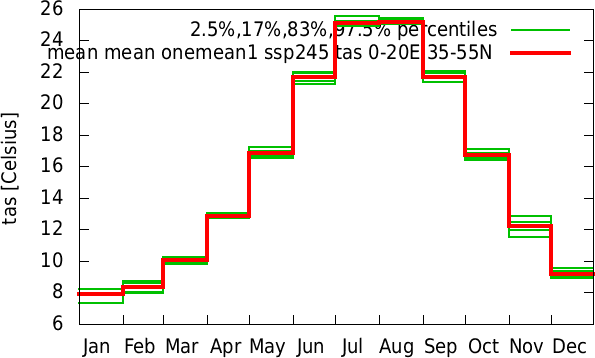

Für 2070-2080:

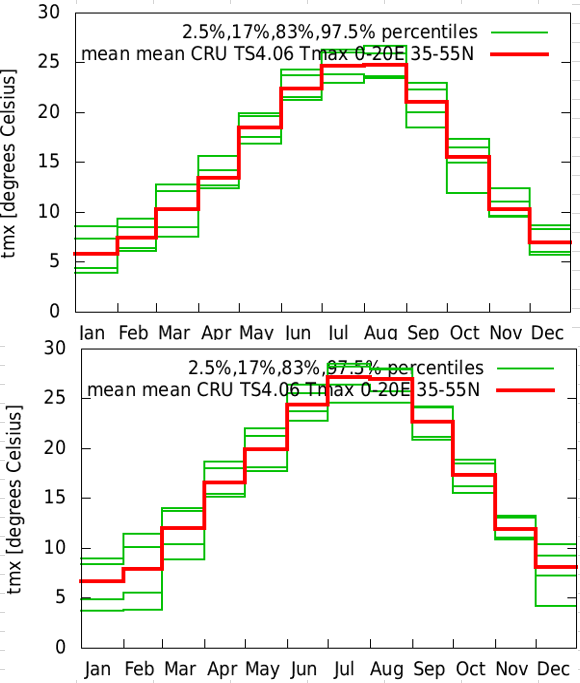

Keine „radikale Wandlung“. Es soll laut Modellen wärmer werden, die monatlichen Unterschiede bleiben jedoch weitgehend erhalten. Da wird die „Silvester-Wärmewelle“ in Europa wohl zu weit ausgeschlachtet. Auch die Aussage „…und das sehen wir schon heute“ ist nicht zu beobachten, jedenfalls auf klimatisch interessanten Zeitskalen. Im Folgenden zeigen wir den Jahresgang der Landtemperaturen in Mitteleuropa. Oben für den Zeitraum 1970…1980 und unten für den Zeitraum 2010…2020. Eine Erwärmung ist zu erkennen (im Sommer z.B. von 25°C auf 27°C, im Januar von 6°C auf 7°C), jedoch keine „Verschiebung“ des Jahresganges. Ist heutzutage alles von der Kunstfreiheit gedeckt?

+++

Leserpost von Dr.-Ing. Bernd Fleischmann:

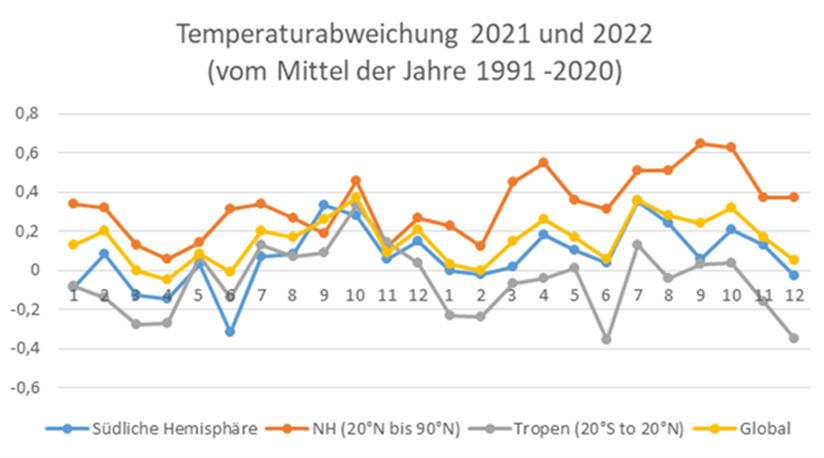

Dr. Roy Spencer hat das Dezember-Update (2022) seiner Temperaturkurve online gestellt. Interessanterweise ist die Temperaturveränderung nicht global einheitlich. Roy Spencer gibt die monatlichen Mittelwerte für verschiedene Breitengradregionen an und eine Auswertung für die letzten beiden Jahre ergibt folgendes Bild:

Sowohl in 2021 als auch in 2022 war es in den Tropen kühler als im Mittel der Jahre 1991 bis 2020. In den Tropen liegen die ärmsten Länder der Erde, von wenigen Ausnahmen abgesehen. An der Temperaturentwicklung dort liegt es jedenfalls nicht und der Spruch „der globale Süden leidet am meisten unter dem Klimawandel“ ist demzufolge fragwürdig.

Mit freundlichen Grüßen

Dr.-Ing. Bernd Fleischmann

+++

Scooty Nickerson, The Mercury News:

California’s snowpack is near a decade high. What does it mean for the drought?

As the New Year begins, California’s Sierra is closing in on the second-largest snowpack we’ve seen at this time of year in the last two decades, with more snow expected to pummel the mountain range in the coming days.

But here’s why it’s far too soon to declare an end to the drought: Last year, we started 2022 with a similar bounty—and then ended the snow season way, way, way below normal.

„We’ve come out hot … but at the same time, it’s really early,“ said Sean de Guzman, manager of the California Department of Water Resources‘ monthly snow surveys.

On Tuesday, state water officials plan to tromp through the snow at Echo Summit, south of Lake Tahoe, for the winter’s first snowpack survey, a monthly ritual that is now mostly for show, thanks to more than 100 sensors throughout the Sierra that measure accumulation every day. It’s of vital importance in the drought-stricken Golden State because officials use the measurements to help manage California’s water supply, which relies heavily on melting snow.

On Saturday, the statewide average stood at a whopping 162% of normal compared to historic averages for this time of year, just eclipsing last year’s figure. But a Bay Area News Group analysis found that of the seven times in the last 20 years that California started the new year with an above-average snowpack, only twice—2005 and 2011—did it finish the snow season in April still above average.

Weiterlesen auf phys.org.

+++

Gregory Moore, Senior Research Associate, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, The University of Melbourne auf The Conversation:

Urban patchwork is losing its green, making our cities and all who live in them vulnerable

One delight of flying is seeing our familiar landscapes in a new way from above. At low altitude most of us know where things are, but as we ascend it becomes difficult to determine the local details, and we begin to see a bigger picture. Sometimes this bigger picture can be scary.

After nearly three years of being unable to fly I have had a couple of recent opportunities to take to the air. My first observation was that in many once-leafy suburbs the green tinge is disappearing under a tsunami of development. You can see this new development on the fringes of towns and cities, as well as redevelopment and infill in the older places. Familiar rows of roadside trees and large old trees that were once suburban landmarks have gone.

As you look from above, it comes as no surprise that the latest State of the Environment report delivered damning findings this week. Vegetation cover in cities is diminishing. So too are the wildlife corridors that once connected now-isolated remnant communities of plants and animals.

Most of you will have heard people describing the view we get from above as being like a patchwork quilt of different colours and land uses, or perhaps like an Indigenous painting that gives us a bird’s eye view of the world below. It shows us a jigsaw puzzle of the disturbed and fragmented environments in which we live.

However, as we soar higher we are reminded that there is only one space, that it is all connected. Each piece of the jigsaw has a place in the big picture.

Cities can’t afford to lose their green cover

Not all green cover has gone in the past few years, but the losses are noticeable. And unless something is done quickly, they will continue. We will reach the point where so many trees are lost that it will jeopardise the capacity of our cities and towns to be resilient, liveable and sustainable in the face of climate change.

No local government can deal with this situation. It is a matter of state and federal planning policy and development regulation.

In most states, for example, developers adopt a scorched-earth policy of removing most, if not all, mature trees from a site before construction begins. State government agencies help deliver treeless sites for development. Expensive government legal teams often fight local community groups opposing tree removals through tribunals and courts.

Vegetation needs to be valued both for the habitat it provides and for the many services it provides to residents of towns and cities. As heatwaves become more intense and frequent, it’s sobering to think the loss of urban trees will result in greater urban heat island effects and more heatwave-related illnesses, hospitalisations and deaths.

Lockdowns reminded us of the value of these spaces

It was fascinating to watch the use of public open space during COVID-19 lockdowns. Concerns about people’s physical health, capacities for coping with stressful situations, increased risks of self-harm and domestic violence, and the learning and development environments of children led to people flocking to their local parks, gardens and riverside reserves.

From the air, though, it becomes painfully obvious that not every suburb or region has many such spaces. It is well known worldwide that people in areas of lower socio-economic status (SES) are disadvantaged by lack of access to treed open space.

This is true of Australia’s cities, regional centres and many country towns where some of the jigsaw pieces seem to be devoid of green. Lack of treed green space is associated with problems such as obesity, poor physical and mental health and social disadvantage.

It’s highly likely people in these areas were further disadvantaged and subjected to greater stress during the lockdowns because of the lack of accessible treed open space. Perhaps this partly explains why some urban areas had lower levels of lockdown compliance than others. There is evidence that the health benefits of access to treed open space are greatest for lower-SES communities.

Public parks and gardens served their purpose admirably during lockdowns. With proper planning, they will do so again in enabling cities to cope with climate change. However, if cities and suburbs keep losing green space and tree cover, their capacity to adapt will be limited. Society as a whole will be the loser.

The mosaic quilt we see from the air reveals just how disconnected the green patches and corridors of our landscapes and urban environments have become. It is astonishing to see developments of large houses on small blocks, which could have been plucked from the new suburbs of any major Australian city, fringing hot, inland towns. There appears to have been no recognition of the effects of a hot Australian summer.

The rapid expansion of Australian cities and towns presents planning challenges in the face of demands to subdivide undeveloped land for housing, countered by demands for connected, treed, public, green space. Providing large and well-connected green space is going to be essential urban infrastructure for increased urban populations facing climate change. It’s not a luxury for a privileged minority, but a vital component of a sustainable economy and environment for all.

+++

Anuradha Varanasi, State of the Planet:

Unraveling the interconnections between air pollutants and climate change

In June 1991, Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines erupted for nine hours, ejecting volcanic ash, water vapor, and at least 15 to 20 million tons of noxious sulfur dioxide gas into the stratosphere. Within two hours, the gas transformed into tiny sulfate mists or aerosols that formed bright clouds. Those clouds spread across the entire Earth and persisted for a year, effectively reducing global temperatures by 0.4 to 0.5 degrees Celsius between 1992 and 1993. Once these cooling aerosols fell out of the stratosphere two years later, global temperatures rose again.

Although microscopically tiny, aerosol particles can have mighty impacts on the atmosphere and climate. Major volcanic eruptions and their resulting aerosol emissions high up in the atmosphere are infamous for altering monsoon circulations and precipitation patterns around the world, even triggering severe droughts in Eastern China and India.

Aerosols created by burning fossil fuels can also impact the climate, although the effects are somewhat different at the ground level. And as human civilizations attempt to reduce their emissions of these harmful particles, they are inadvertently generating unwelcome side effects, too.

Understanding aerosols

Ever since the first Earth Day was observed in 1970, the global average temperature has been accelerating at the rate of 1.7 degrees Celsius per century. Before 1970, the rate of warming was only 0.01 degrees C per century. At the current rate, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warned that the average global temperatures could rise by more than 2 degrees Celsius by 2100, which would unleash devastating impacts on the planet.

„When we talk about the causes of human-driven climate change, a lot of attention is given to greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane, but the anthropogenic aerosols component is rarely mentioned,“ said Scott Barrett, a vice dean at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and the Lenfest-Earth Institute Professor of Natural Resource Economics.

Aerosols (also known as particulate matter or PM) are a mix of suspended liquid and solid particles in the air with distinctive chemical compositions. The smaller the size of an aerosol, the more severe its health impacts. Particulate matter with a diameter of less than 2.5 microns (PM2.5) can easily infiltrate the lungs. PM2.5 has been associated with higher rates of respiratory, autoimmune, and neurological disorders than a comparatively bigger PM with a diameter of 10 microns or less—also known as PM10.

Weiterlesen auf phys.org.

+++

Bob Yirka , Phys.org:

Net-zero carbon emissions for aircraft overlooks non-CO2 climate impact

A trio of researchers, two with the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology’s Department of Environmental Systems and the other with Climate Service Center Germany, Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon, say that reducing CO2 emissions from aircraft will not fully solve the problem of their negative climate contributions. In their paper published in the journal Nature Climate Change, Nicoletta Brazzola, Anthony Patt and Jan Wohland note that other emissions from aircraft also contribute to climate change.

As climate change progresses and governments around the world fail to enact measures to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions, scientists continue to look for ways to address the problem. In this new effort, the researchers are pointing out to both the science community and governmental officials that forcing aircraft makers to reduce or eliminate CO2 emissions from the planes will not eliminate their carbon footprint. In addition to CO2, the researchers note, jet airplanes have an indirect impact on the climate—they create contrail cirrus, which contain aerosols, soot and water vapor that incite changes in O3, CH4 and water levels in the stratosphere due to NOx emissions. Together, these emissions account for enough warming to heat the planet by an additional 0.4° C in the coming years.

The researchers note that emissions besides CO2 from aircraft are not currently being discussed as part of global warming mitigation efforts to reach the goals set by the Paris climate agreement—and failure to do so will likely perpetuate the negative indirect impact of aircraft on global warming. They suggest including plans for reducing or removing harmful elements from the contrails left behind by jet aircraft flying in the stratosphere.

Weiterlesen bei Phys.org